From the time of the 19th-century gold rush, the Gulflander train has carried passengers between the remote towns of Normanton and Croydon.

Still going strong, the ‘train from nowhere to nowhere’ now treats visitors to a memorable Savannah rail journey. The Gulflander rail journey is a living embodiment of the phrase; “It’s about the journey, not the destination.”

The quirky history of Normanton in Queensland’s Gulf Country

I’m walking to Normanton’s railway station, when my eye is caught by Krys the croc. It’s a life-size fibreglass model of the largest crocodile ever to be shot in Australia. It’s hard to ignore at 8.63 metres in length. As well as being terrifying, it tells a story about the frontier nature of this town in the Gulf Savannah region of northwest Queensland. The original Krys was taken down in 1957 by Krystyna Pawlowski. She would later come to regret that fatal shot and became a conservationist in partnership with her husband Ron. In the 1970s they helped convince the Australian Government to ban the hunting of crocodiles.

There’s always been a tension between nature and development here in Normanton. It was this remote town that inspired Nevil Shute’s novel A Town Like Alice. At one point it was expected that Normanton would become the next big tropical city, another Darwin. Instead, it remains a sleepy settlement of about 1200 people. It has good historical bones though, with some impressive colonial buildings along with the Purple Pub (painted that lurid colour all over) and the Big Barra, a statue of the famous local catch.

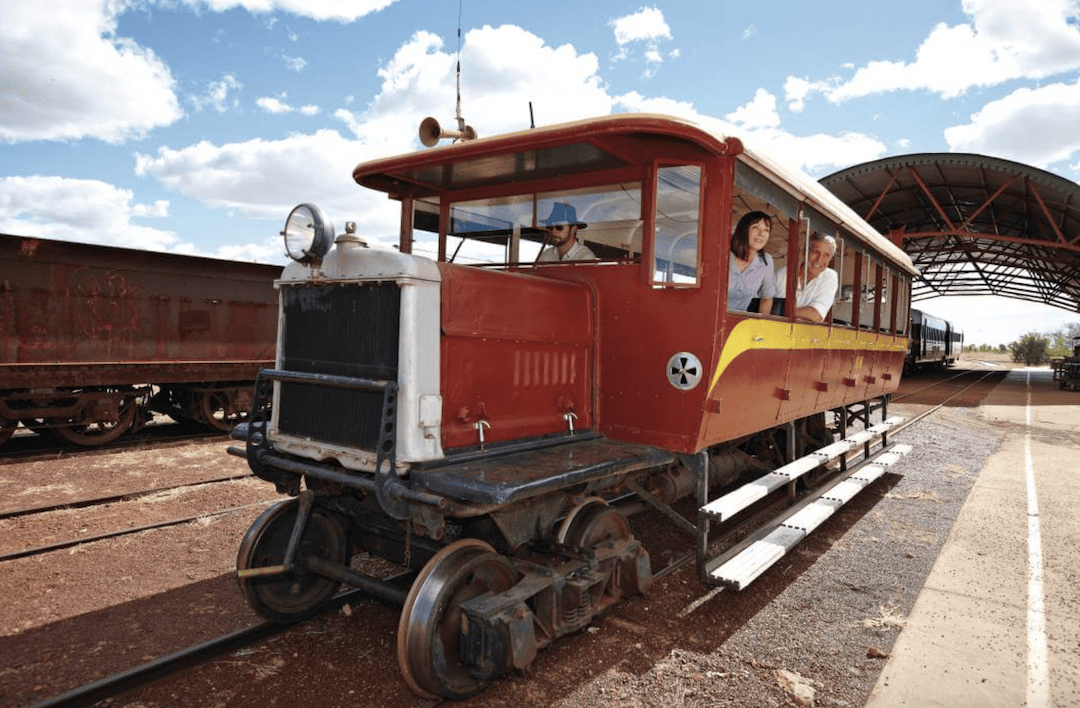

I’m in town to catch a train from the attractive station that’s set within gardens like an old farmhouse. Here I find the Gulflander waiting beneath a corrugated canopy. Its engine is running and frame vibrating as the crew ready it for departure.

A life for the Gulfander after the gold rush

Remarkably, this remote railway has been in operation since the late 19th century. Originally laid south toward Cloncurry, it was diverted to inland Croydon after the start of that town’s 1885 gold rush. Having survived a major flood in 1974, the Gulflander hung on to become a quirky tourist train.

What helped it last so long was the railway’s unusual track, whose arched steel sleepers allowed the rails to sink solidly into the ground. This innovation meant the train could keep going in up to 15 centimetres of water. This was a huge benefit in a region often hit by heavy wet season rains.

“Gold is long gone, but the train survived because it could still get through floods,” says stationmaster and driver Ken. He eases our maroon and gold engine, with its attached passenger carriage, out of the station.

It’ll take five hours, including a tea break, to cover the 150 kilometre route to Croydon. The journey is a weekly Wednesday run (returning to Normanton on Thursday). As it’s so early in the train’s operating season, there are only four passengers aboard. My fellow travellers are a family group from Sydney who tell me they’ve often travelled together to interesting railway experiences. I’m sensing that this remote rail journey – dubbed ‘the train from nowhere to nowhere’ – is a magnet for rail enthusiasts.

The journey from nowhere to nowhere

We passengers spread out, each taking one of the reddish-brown bench-style seats, next to sliding windows framed by maroon curtains. There’s a distinct vibe of 1950s school bus about the interior, especially with Ken in the cabin with us, sitting up front on the right.

As we bump along the rails, passing the airport where maintenance workers give us a friendly wave, Ken adds commentary via a hand-held microphone. “You’re lucky to be here this time of year, as the countryside is still very green. Later in the year it’s brown – still beautiful, but not as green.” It does look lush and well-watered as we leave town, passing slender gutta-percha trees with dark trunks. Above us is a big sky of light grey cloud, made luminous by hidden sunlight. Suddenly a black-necked stork takes flight in front of us. Then I spot a group of brolgas by the rails, flying off as we approach. Later on, a group of plains turkeys scatter.

It seems our fate to scare birds into flight. The unpeopled landscape may be serene, but this is the noisiest train I have ever ridden in. Growling and rattling as it passes along the rails, the track has sunk into the soil in parts.

Critters Camp and special Gulflander excursions

In addition to its weekly trip to Croydon, at the height of tourist season there’s a shorter jaunt to the colourfully-named Critters Camp, along with other special excursions. As we pass that location, a small wallaby tears across the front of the train. I also spot a few cattle by the line, mostly Brahman. It reminds me that the cattle industry is a mainstay of the local economy.

At Blackbull we stop for tea and blueberry muffins. This site once had a refreshment room, and a camp for rail maintenance workers. Its shed is the first railway building I’ve seen since leaving Normanton.

“In 1943 the station building was destroyed by a storm, and its remains were used to build this shed,” said Ken. Another reminder of the power of nature in the Gulf Savannah country.

A rickety arrival into Croydon in Gulf Country, Queensland

Back in motion, we pass paperbark trees, in blossom from recent rains. Ken also points out the bloodwood tree, the tallest in the region. We’re almost to Croydon now, passing an abandoned townsite, Golden Gate. In its gold mining heyday it had 1500 residents, and additional ‘suburban’ train services to and from Croydon. There’s nothing to be seen now, beyond a scattering of abandoned mining machinery.

Nearing the end of our journey we ascend True Blue Hill, named after a former mining company. It’s the steepest point on the route, but we pause to let a couple of cows cross first. Then Ken eases the Gulflander into Croydon’s station, a simple metal structure built in 2005 after termites destroyed its predecessor.

Croydon is even smaller than Normanton. Though the railway reached the town in 1891, the gold which prompted its construction quickly ran out. By 1933 Croydon had only 226 residents, and it’s not much bigger than that today. But it’s been lucky in inheriting some interesting architecture from that long-lost golden age. And of course, it still has a weekly train service. Like Croydon, the Gulflander is a happy survivor: a strange little train which has endured, when logic suggested it should not. I’m glad I’ve been able to catch it to nowhere.

Tim Richards travelled courtesy of Queensland Rail Travel. For fares and bookings on the Gulflander, see gulflander.com.au

To discover more must-do outback trips, click here.

Travel to Normanton

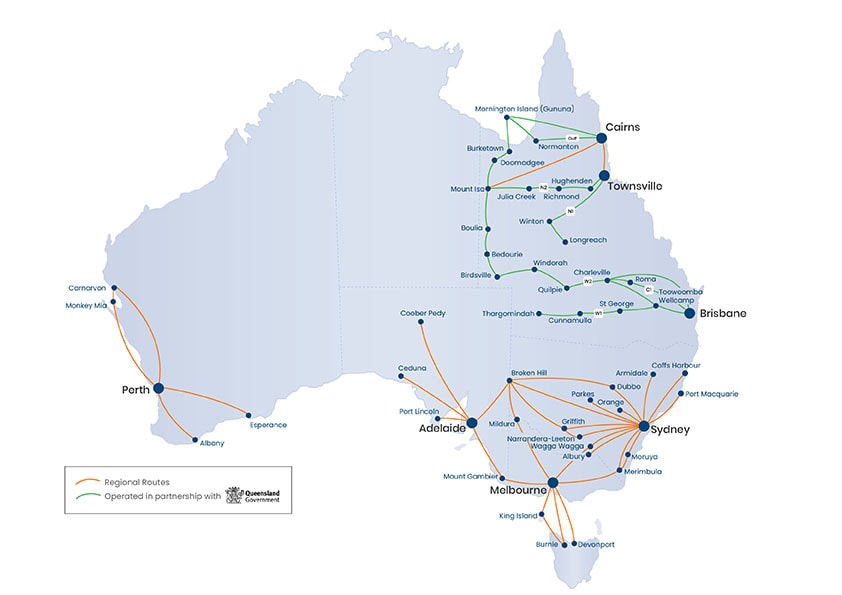

Rex flies to Normanton. Book your flights here and check out the route map below for more inspo.