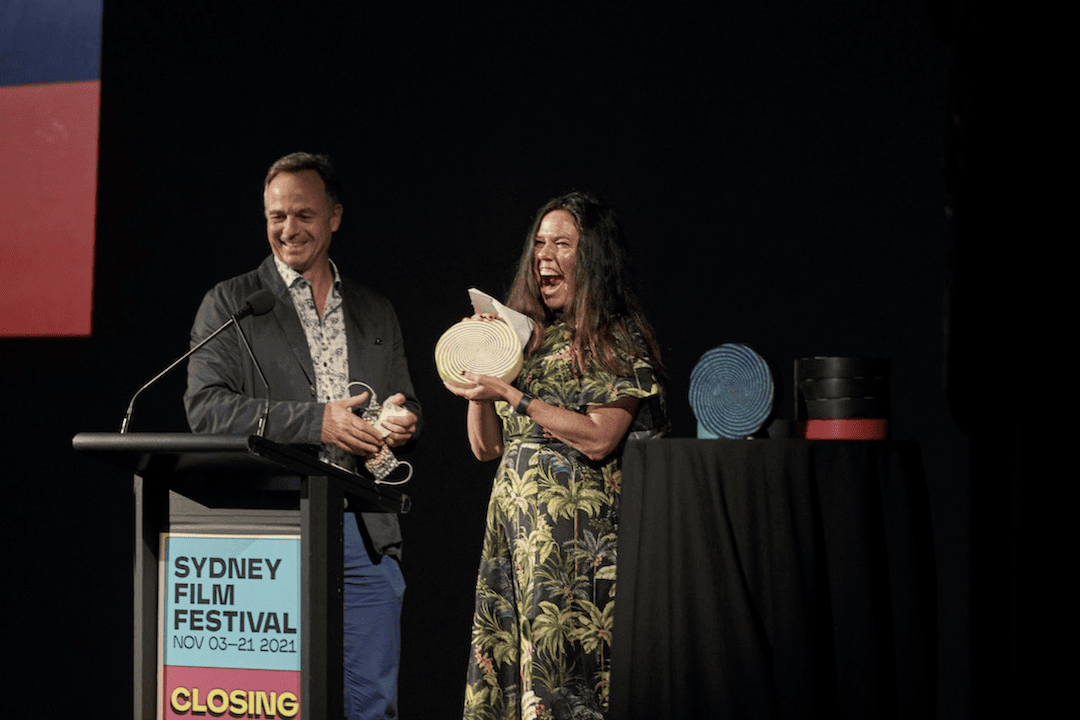

Darlene Johnson won the Deutsche Bank Fellowship for First Nations Film Creatives in 2021 and has been writing and directing award-winning film and TV for over 20 years. We spoke to Darlene Johnson about her amazing career in film.

When did you first become interested in working in film/TV and what was your path to pursuing it as a career?

My first foray into film and television was being accepted into the inaugural From Sand To Celluloid initiative by the Australian Film Commission. It was to support emerging Indigenous creatives in making their own short films, and to create a pathway for mob to enter the industry. I fortunately won a placement with my project, which was a little anecdote about my mother who used to pass for white at the local swimming pool in country New South Wales. It became the short film Two Bob Mermaid. I didn’t have the technical skills then but I had my passion, my instincts, my mother’s story and my mother’s spirit. I guess you can say that my passion really started with a kind of political motivation to tell our own unique stories and put our own voices and stories up on the screen. You’re like a guardian for that story and you’re protecting it, because it really is a sacred thing.

Your work centres Aboriginal voices, culture and history, and you are passionate about Aboriginal representation in film. What does it mean to you to share these stories?

Two Bob Mermaid was the very first film that depicted fair-skinned Aboriginal people: you know, people that look like me, because we didn’t really have those portrayals and representations on television. You would never see a blackfella on Home and Away or Neighbors when I was growing up! I was also interested in looking at the complexities of what it means to be Indigenous and fair-skinned, and the politics of that – but in a dramatic way, an emotional way, not an academic way. As a blackfella, you’re very conscious of the struggle and your place in the world. You recognise when there’s no recognition, or you’re invisible or when you don’t have a voice. That actually does engender a particular point of view and sensibility when it comes to art and telling stories. What’s exciting is when we get to imbue it with our own sensibility or our own personal experience. Everyone has got a really different story, which is pretty cool.

You are a fantastic documentary filmmaker, with films like The Redfern Story receiving a Walkley along with many other awards. What do you enjoy or find challenging about documentary filmmaking?

I think the best thing for me is being able to go right around Australia and meet all the different mobs who come together around a collective situation or issue, and all be driven and passionate about it. They’re trusting you with their story and you need to totally respect that they are primary to the whole filmmaking process. For The Redfern Story, that was 40 years since the National Black Theatre was actually set up in Redfern and a lot of that mob had passed, but the remaining survivors were the ones that I was able to interview for the film. It was important to be able to look at a snapshot of our history and the positive legacies of blackfellas, to counter not only invisibility, but also negativity. The best part about documentary filmmaking is going on that adventure and journey of discovery. If you know what you’re doing beforehand, then there’s really no point or much fun in doing it. It’s through the process that you actually work out what it is that you’re making. The story is like a little puzzle that starts to come into alignment.

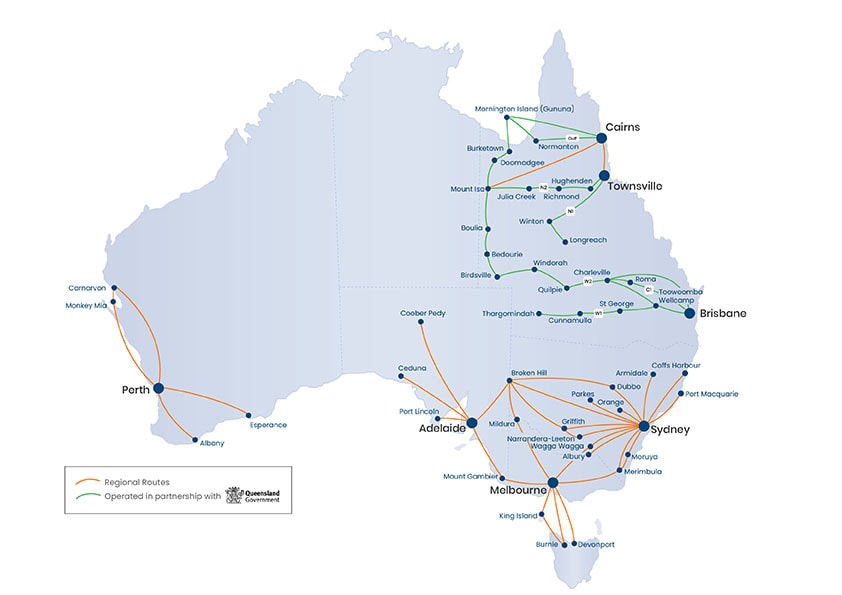

Much of your work has taken place in remote Aboriginal communities such as Ramingining in Arnhem Land where you filmed your documentary on the great Indigenous actor David Gulpilil. What is it like shooting in these remote communities and how do you need to adapt your filmmaking process?

Working in remote Arnhem Land with the iconic David Gulpilil was amazing. It’s what I call blackfella filmmaking. You’re working within the cultural fabric of a community. So it’s not about just affiliating yourself with one person; you’re consulting with a whole group of people. Culture is primary. People live a pretty traditional existence out there, and you’re involved in traditional kinds of activities and practices. You’ve got to tune into a whole different way of life, and how people live and speak to each other and relate to each other, and how a community is organised and decisions get made. You learn what you can and can’t do and what’s appropriate, and what isn’t. You’re learning language, culture, spirituality. So it’s all about being super open and sensitive to a different cultural way of doing things.

What’s next for you in your film career?

I’m expanding on my short film Bluey, and developing it into a feature film. So that’s really exciting, because that’s very current and relevant – it’s about a young girl in incarceration, but it’s more a positive redemption story. I’ve got my own TV series that I’m in the process of developing, which is the one that’s attached to the First Nations Fellowship. It’s a supernatural crime thriller, and it’s inspired by my own Aboriginal ancestry, but also my life as a documentarian.

Where would you love to travel in Australia?

I definitely would love to go to Arnhem Land, and catch up with David’s family up there. They gave me a skin name and I’m part of that family too. I’d love to go spend some time out bush with mob, just singing songs and telling stories around the fire.

To read about more Aussie icons like Darlene Johnson, head to our Aussie Stars page!